This historic and groundbreaking symposium was a great success, attended by more than 120 NAWCC members, conference speakers, and local students. Professional video recordings of the entire program soon will be available for loan and viewing from the NAWCC. Many thanks to the participants and to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for hosting the event and for agreeing to allocate a large portion of our facilities rental charges to a horological acquisition or restoration.

Photos by Robert C. Cheney and Katie Knaub

Report and Summary of the Horology in Art Symposium

By Katie Knaub

The 2017 Ward Francillon Time Symposium, "Horology in Art", held at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts from October 26th to 28th, focused on a unique theme. The presenters explored the purpose or context of horological pieces in a variety of genres of the visual arts in which they are found. This was the first ever conference anywhere in the world on this subject.

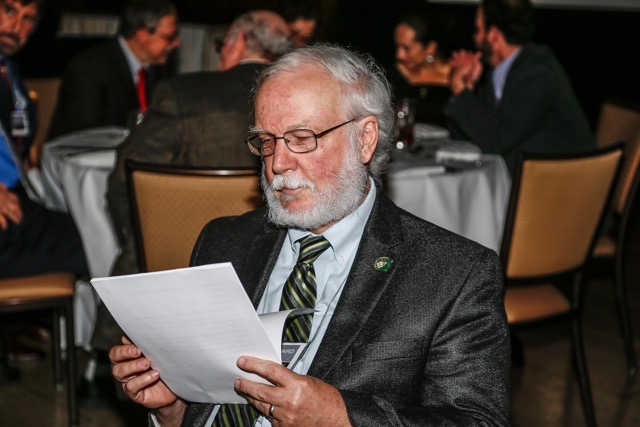

The educational event, organized by Symposium Chairman Bob Frishman, was three years in the making and included 18 eminent art historians, curators, scholars, and horologists who came together to explore timepieces in remarkable and, at times, unexpected ways.

Thursday, October 26th

Beginning on Thursday afternoon, forty attendees who arrived early had the opportunity to join a one-hour tour with Lana Sloutsky, Ph.D., History of Art & Architecture Department, Boston University. On this tour, they viewed a selection of exceptional horological pieces, including pieces by William Claggett, Lemuel Curtis, Simon Willard, Thomas Tompion, and Higgs & Evans. These were currently on display in several of the museum’s American and European galleries. Dr. Sloutsky, also a seasoned gallery instructor at the museum, explained the context of the horological pieces within the arrangement of other decorative arts of the period in which they are exhibited. The objects viewed can be seen online through the MFA’s database and included a Butterfield sundial, Claggett tall case clock, Willard girandole wall clock, German table clock, French mantel clock, Simon Willard lighthouse clock, Lemuel Curtis girandole wall clock, John Townsend tall case clock, Spanish astrolabe, bracket clock, Thomas Tompion tall case clock, David Evans and Peter Higgs Jappaned tall case clock , and Jaffrey parlor tall case clock.

The formal program began Thursday evening in the Alfond Auditorium with Chairman Bob Frishman’s introduction of the symposium background and theme. He introduced both of the evening’s speakers and offered a history of the James Arthur lecture. Attendees were delighted to learn that most of the room’s rental fee would be used to directly support conservation of the horological collection at the museum.

Dennis Carr, Museum of Fine Arts curator, presented an overview of the American clocks in the collection on exhibit and in storage. He highlighted some of the museum’s visual arts that incorporated clocks; including quilts, paintings, and Christian Marclay’s “The Clock” (2010), a contemporary art piece of clocks in motion, which literally becomes a functioning timepiece when shown.

The James Arthur Lecture, which has been the keynote of the NAWCC Time Symposium since 1984, was delivered by eminent American art scholar and Princeton University Professor John Wilmerding. He explored the varying concepts of time in American painting by examining the changing artistic movements of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. He discussed several artists including Thomas Eakins, John George Brown, Fitz Henry Lane, John Peto, Frederick Church, Gerald Murphy, Robert Indiana, and Jackson Pollock, giving examples of how each interpreted time or the passage of time and how the interpretations varied with the artist movements of the periods discussed. He touched upon several instances of timepiece symbolism in artworks, including measurement of human life cycles. This theme would reverberate with other presenters. Dr. Wilmerding posed a thought-provoking question at the conclusion of his presentation which reflects the digital age we now live in. He wondered about the terms clockwise and counter clockwise and whether our youth soon will not know these terms anymore.

Friday, October 27th

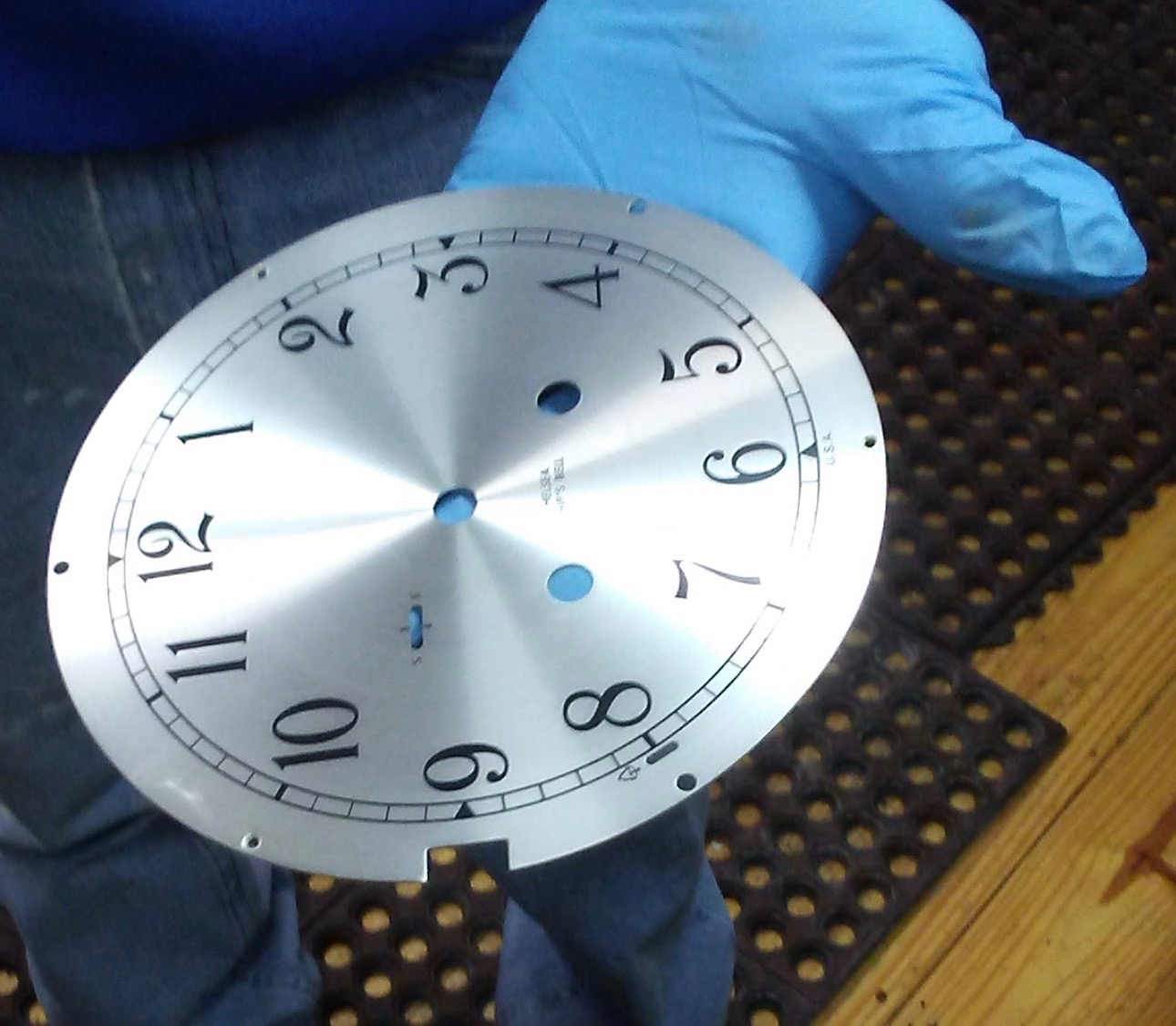

Before the formal presentations began Friday morning, a small group of eleven participants had the rare opportunity to tour the Chelsea Clock Company, just a short drive from downtown Boston. The tour highlighted the new building that the company moved into two years prior, a mere two blocks from its original location of 118 years. Marketing director Patrick Capozzi led the group and allowed the group to see the complete clock-making process, ranging from utilizing modern CNC machines and hand-silvering of dials to the assembly of their famous “Ship Bell’s Clock” model.

The company’s detailed log books line the assembly room and contain records of each and every clock produced by the company. The entries include not only when the clock was made and who boughut it, but also notate any service work Chelsea’s repair department may have performed on the timepiece. Robert Ockenden, master clockmaker for Chelsea, described a new initiative the company is developing for an in-house training program for future horologists to keep the craft alive.

Friday’s presentations began with MFA curator Tom Michie’s overview of the European timepieces in the Museum of Fine Arts. He highlighted all the pieces within the collection noting that this presentation gave him the opportunity to revisit the horological pieces under his care, including those housed in off-site storage. Examples ranged from a 1550 sandglass, 16th century Italian lantern clocks, and even a fake Thomas Tompion. The complete horological collection (both American and European) can be viewed and searched on the museum’s online database.

Lawrence Berman, MFA curator of Ancient Egyptian, Nubian, & Near Eastern Art, discussed how ancient Egyptians kept time and how it was reflected not only in the visual records they left but in the actual timekeeping devices as well. He explained the ancient Egyptian calendar system and problems associated with its failure to include leap year corrections. Berman noted that obelisks were not used for telling time in Egyptian civilization, although they may have been used by other civilizations for that purpose. Rather, examples of personal sundials dated 1200-1184 BC were found during a 2013 dig in workmen’s huts in the Valley of the Kings and would have been used to track the eight-hour workday historians believed existed in Egypt at the time. Decoratively carved water clocks, commonly featuring a baboon (symbol closely associated with Thoth, god of wisdom, science and measurement), were used for religious purposes. Berman shared examples of both personal devices, such as sundials, as well as timepieces, such as water clocks, that were utilized for religious purposes.

Dr. Lana Sloustky then explored the Byzantium civilization’s method of timekeeping. Byzantium was dominated by the church and the timekeeping devices utilized were tied into the scheduling of religious services. Most of the timekeeping devices, sundials and obelisks, were for the public. Few horological devices from this period exist but some such as the Gaza clock were described in writing from the period. In the Museum of Science’s (London) collection, there is a Byzantine portable universal altitude sundial with geared calendrical device, that could be adjusted for the time of year. Dr. Sloustky shared a video with attendees which replicated Byzantium monks’ call to prayer, not by the chiming of a clock, but of the hitting of a semantron, an iron bar gong that is struck by a mallet.

Philip Poniz, horological expert, discussed the depiction of clocks and watches in Renaissance art and why the timepieces were included in the portrayals of scenes in which the timepiece would not have normally existed. Renaissance art featured timepieces in prints, paintings, manuscripts, statues, frescos, and tapestries. Poniz hypothesized that in many of examples he gave, clocks were included not to represent reality, but to convey some other message, although the artist’s meaning is sometimes impossible to convey unless the sitter of the work is known. Although meaning may be difficult to determine, the artwork itself is beneficial in placing into historical context when clock styles and types developed. For example, the square clock was thought to be much later, but earlier paintings with depictions of square clocks show it actually to be earlier.

Dr. Philippe Bordes, University of Lyon, examined clocks in French portraits from the late 1700s to the early 1800s and suggested that the inclusion of clocks was used to represent a social, cultural, or moral status. Bordes focused on two works in detail, Madame de Pompadour’s portrait (1756) by François Boucher and Jacques-Louis David’s 1812 portrait of Napoleon. Madame de Pompadour’s portrait features an ornate mantel clock in the background and conveys the style and taste of the French court at the time, while subtly expressing the virtue of punctuality of the period. The inclusion of the clock in David’s work plays a key role. The scene depicts Napoleon after he worked through the night writing the historically important Code Napoléon. It was after four o’clock in the morning as the tall case clock in the background illustrated. Jonathan Snellenburg, from Bonhams in New York City, then gave an impromptu explanation of French clock production at the time that it was featured in the works on which Dr. Bordes presented. He emphasized the clock case was the center of study for clocks of the period as the movements were interchangeable.

Johnathan Snellenburg’s own presentation focused on the decoration on watch cases from the 1500s to 1800s, and how the appearance of the watch was more important than the function of the piece. He cited examples of enamel decorations and the artistic scenes that were represented on watch cases. Snellenburg gave a short history on the technological development of the watch from its 1500s ancestor, the drum clock, to the watch pendant and how the innovations in watch technology allowed for a medium to include highly decorative scenes such as those found during the 17th century. He also illustrated the evolution of watch case decoration to the decoration of similar personal items like 18th century snuff boxes.

Louise Cooling, Curator at London’s Royal Collection Trust, explored genre paintings of the Victorian period through examples by Frith, Hunt, Redgrave, Cope, Holl, Walton, and Spencelayh. Cooling examined how 17th century Dutch genre painters influenced these Victorian painters. She also discussed the influence of literary works of the period on these artists. The timepieces featured in the works served as a symbol of the brevity of life or the fleeting nature of time, a theme shared by other presenters.

Colleene Fesko, appraiser, broker, and independent curator, concluded Friday’s program by discussing the interpretation of time in the work of female surrealist artists and how the perception of time between men and women is different. Fesko chronicled the development of surrealism first as a literary movement, then as a visual form. She examined works such as Remedios Varo’s The Clockmaker (1955), Frida Kahlo’s Time Flies (1929), and Helen Lundeberg’s Double Portrait of the Artist in Time (1935). The artists who were discussed shared a common theme of clocks as a symbol for time running out.

Saturday, October 28

The program on Saturday began with Dr. Catherine Pagani, The University of Alabama, exploring clocks of the Chinese Qing dynasty and the European influence on the clocks given to the court during this period. She noted that the trade of clockmaking also was taught to the Chinese by the Jesuits. The clocks of this period were viewed by the court as a status symbol or as decorative art, rather than as timepieces. Dr. Pagani shared videos of two clocks with their automata elements in motion; these videos were quite spectacular to watch and hear. She chronicled the unfortunate loss of many of the clocks of this period due to the 1860 sack of the palace by Anglo/French troops, the Boxer Rebellion, and 20th century political upheaval. Today there remain about 1500 clocks and watches at the Forbidden City, with roughly 200 on display.

Dr. Ross Barrett, Boston University, focused on James Henry Beard’s antebellum painting The Land Speculator and the symbolism of the two clocks featured in the piece. The timepieces serve as a symbol of the conflicting constraint of time during the period, when time became more regimented in society. The empty hanging clock case on the wall could serve as a representation of the perilous land speculation of the 1830s. The clocks incorporated into genre painting of this period show how former luxury objects became middle class goods during the antebellum period. Barrett offered John Whetten Ehninger‘s Yankee Peddler (1858) as an illustration of this transformation of object from one class to another.

Amy Kurtz Lansing, Curator of the Florence Griswold Museum, discussed the genre paintings of Edward Lamson Henry including The Old Clock on the Stairs based upon Longfellow’s poem of the same title. The location of the tall case clock on the landing of the stairs, rather than in the living chamber, signals a change in the social status of these objects from one of prominence to old-fashioned as society made way for more modern technology. The clocks also have new symbolic meaning in this post-antebellum era. Rather than time as a burden, she described the Quaker influence, most likely from Henry’s time spent studying in Philadelphia, as an opportunity of “redeeming time” or to use it well. She also drew on Henry’s personal collection of timepieces and how those objects may have influenced his work. Horological expert Robert Cheney extemporaneously gave some historic background on the clocks featured in Henry’s work as well as those in the photographs of Henry’s personal Americana collection.

Dr. Stephen Caffey, Texas A&M University, gave a presentation on the Winslow Homer watercolor Winding The Clock. The work was purchased by a Civil War officer and exhibited at an 1881 watercolor show in New York. The work serves as an example of Homer’s focus on the “new woman” of the late 1800s and the euphemisms surrounding the inclusion of the clock and winding key in Victorian society at the time. Caffey also offered other examples of Homer’s work from the same period which featured women as the subject and also offered support to Homer’s attempt to highlight the “new woman” struggling against a patriarchal society.

The final presentation of the afternoon was a collaboration between Peter Sorlien, appraiser, and William J. H. Andrewes, horologist, exploring how the technological developments of clocks coincided with the development in printmaking. Sorlien offered a chronological review of forms of printmaking, while Andrewes discussed the horological devices featured in the works presented as examples. Sorlien discussed printing techniques from copper plate engraving, etching/dry point, wood block printing, to steel engraving and lithography and the processes involved in producing works from those methods. Examples of those techniques included illustrations of various forms of horological devices from the water clock, sundial, and mechanical clock, to Japanese temporal hour clock, which gave Andrewes the opportunity to discuss not only the mechanics of those devices but, as other presenters had done, commented on the timepieces depicted in a scene.

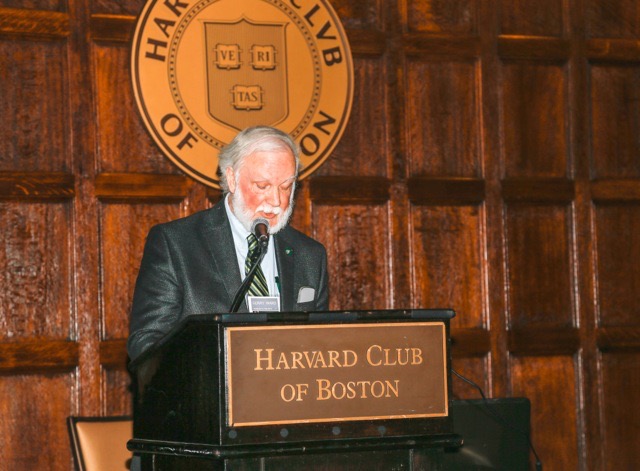

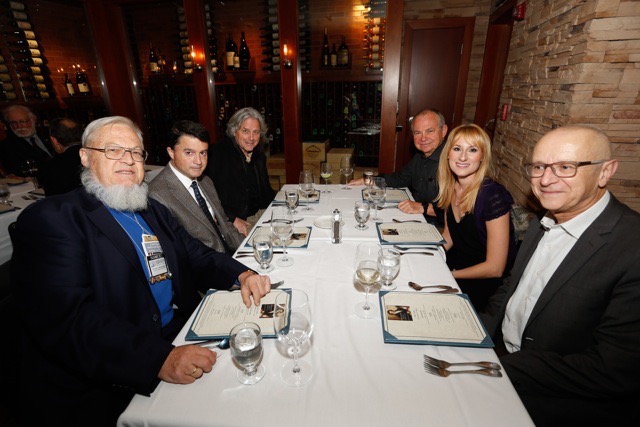

Saturday evening symposium attendees gathered at the historic Harvard Club of Boston for a culmination of the program with dinner and live musical entertainment featuring a performance of time-related songs. The evening included an unveiling of an artistic work, Man With Time on His Hands, by Pat Keck (who’s work readers may learn more about in Bob Frishman’s article in the NAWCC’s Bulletin, No. 431 January/February 2018). MFA curator emeritus Gerald W.R. Ward provided an examination of how the museum as a public institution serves as history’s clock. Dr. Ward discussed how museums mark the passage of all forms of time. They communicate about the past to help visitors answer the questions of where do we come from, who we are, and where we are going.

Sunday, October 29

Attendees who extended their stay had the opportunity to experience a personal tour of the Harvard Scientific Instrument Collection by curator Dr. Sara J. Schechner and Richard Ketchen, horologist for the museum. The collection of over 20,000 early instruments of all area of the sciences is viewable and searchable online. It includes a suite of clocks that highlights the progression of accurate timekeeping from Tompion to the Shortt-Synchronome clock system. Dr. Schechner shared some stories of the objects, noted that the collection contains the largest group of sundials in North America, and reported that during the colonial period Harvard students were taught how to make sundials as part of the curriculum. In 1764 a devastating fire destroyed Harvard Hall and with it most of Harvard College's collection of scientific instruments. Individuals and organizations assisted in the rebuilding of the library collections and scientific apparatus. One donor, Benjamin Franklin, purchased a new astronomical regulator in 1765 by John Ellicott to replace “the old Tompion”.

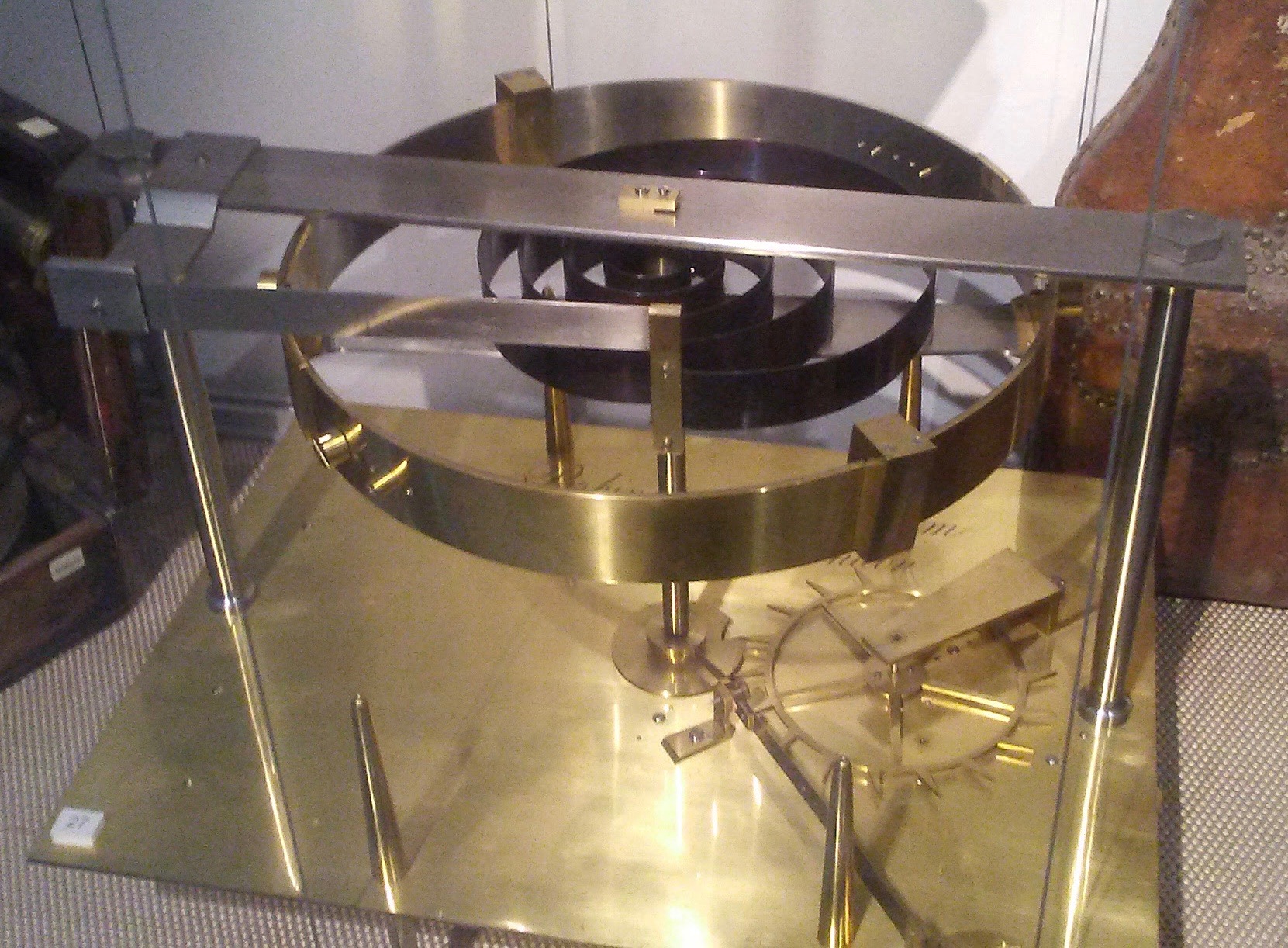

Attendees also had the opportunity to tour the nearby “Philosophy Chamber" exhibit currently at the Harvard Art Museum. Amy Torbert, the 2017 Maher Curatorial Fellow of American Art, discussed the mechanics and historical context of the orrery by Joseph Pope which was housed in the Philosophy chamber of Harvard in the late 1700s and early 1800s. The Philosophy Chamber was an ornately decorated room at Harvard Hall and the collection housed in it played a vital role in teaching and research at Harvard. The exhibit attempts to recreate the Philosophy Chamber utilizing objects known to have existed in the building during this period. The Pope orrery was one of those objects. Begun in 1776 and finished in 1787, it is one of only five known instruments made by Joseph Pope, a Boston clockmaker. In 1788 a group of prominent citizens tried to purchase the orrery for Harvard or persuade the college to buy it. Members of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences petitioned the General Court of Massachusetts for permission to hold a lottery to raise money to buy the orrery. After this exhibit closes, it will return to its usual display in the Harvard Scientific Instrument Collection.

The depth and breadth of programming at this year’s Symposium was impressive, covering a wide range of not only timepieces, but also art forms. This synopsis alone cannot give justice to all the great speakers and programming that attendees enjoyed during the three-day event. Professionally produced video recordings also may be viewed via the NAWCC website or borrowed on DVD.