HOROLOGY IN ART

In 1954, the renowned Swiss scholar Alfred Chapuis (1880-1958) published De Horologiis in Arte. The 154-page book now is somewhat rare and costly, its text is in French, and its 212 illustrations are in black-and-white.

In 2005, an exhibit — “La misura del tempo”— in Trento, Italy, featured the rich history of Italian horology. Its 669-page exhibit catalogue, written in Italian by Guiseppe Brusa, included many full-color plates of artworks depicting clocks and watches. Also since 1954, other horology historians have sometimes noted fine art images showing timekeepers, but not in the same focused and intensive way as Chapuis, and now me. A culmination will be the “Horology in Art” conference I am organizing as Chairman of the NAWCC Time Symposium Committee, October 26-28, 2017, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

My interest in horology images first ignited as a collector of old stereoscopic photographs. In the 1990’s, I began to collect 19th century 3D cards showing clocks and watches (Fig. 1), and I published two articles about this in the NAWCC Bulletin in April, 2002, and June, 2007. I also discovered that some photographic studio portraits by the famous American photographer Mathew Brady (1822-1896) included a “Reaper” model cast-metal figural mantel clock (Fig.2). I wrote about this in the October, 2002, NAWCC Bulletin. My collection of original stereoviews and Brady photos, all with clocks in the scene, now numbers more than a hundred examples.

Most of these vintage photographs are not recognized as fine art, but instead as documentary records of people and places. Paintings, dating back to the 13th century origins of mechanical timekeeping, more truly represent “horology in art.” My attention to those artworks began with a Renaissance painting by Bolognese artist Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) of an African woman posed with a German gilt-metal table clock (Fig.3). It appeared in a 2005 Christie’s art catalogue, and I obtained permission from the auction house to reprint it on the back cover of the February 2006 NAWCC Bulletin.

From then, I began my search for more such fine-art images. I quickly realized that the clocks and watches in these paintings were not there by accident, but were included as symbols and metaphors for affluence, sophistication, discipline, and human mortality. Although valuable to present-day horologists who can learn from period views of timekeepers, those paintings were not done to advertise horology, but to include timekeepers as important characters in the narratives of the pictures.

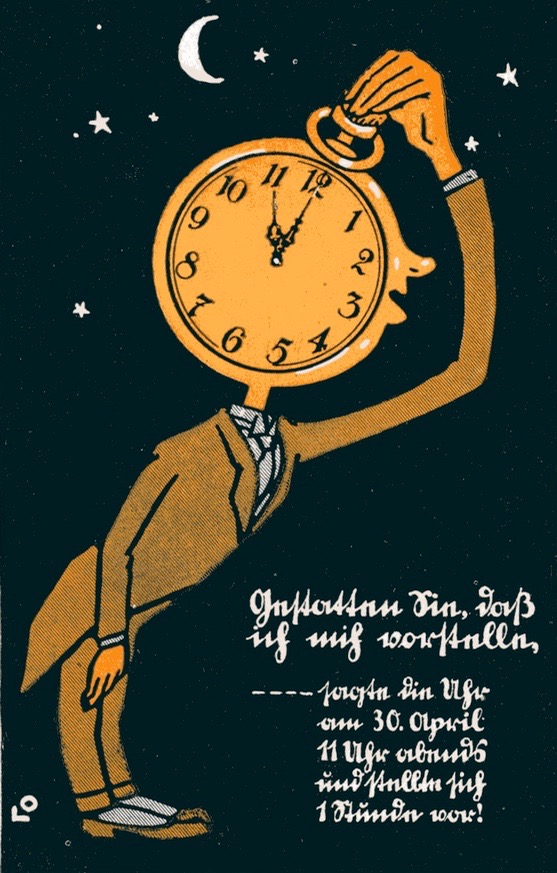

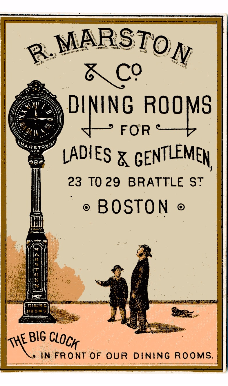

My computer now stores nearly 1300 “horology in art” digital images. This may sound like a large number, but such artworks actually are quite uncommon. Most often, I find none when studying auction catalogues and art books, and when scouting museums. Some of my images may be better described as illustrations — trade (Fig.4), greeting, and post cards (Fig.5), for example — or they are early photographs, which were not produced for artistic reasons.

Many hundreds of my images, however, truly deserve to be termed “fine art.” My roster ranges from Albrecht Durer to Rembrandt, from Titian to Van Gogh, from Winslow Homer to Marc Chagall to Jamie Wyeth (Fig.6). At the 2011 NAWCC convention, I presented a lecture on “Horology in Art.” In March, 2012, I initiated a “Horology in Art” series of articles for every issue of the NAWCC magazine. The next article, at the time of this writing, will be Part 30. All the articles may be viewed via my website page — http://bell-time.com/articles/articles.html .

My first article presented The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries (Fig.7) by Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). David was the foremost painter of his era, and unquestionably one of the best of all time. His large 1812 oil-on-canvas, now on view at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., was commissioned by a Scottish nobleman who greatly admired Napoleon. The elegant standing regulator, unsigned but possibly by Janvier, indicated that the Emperor has worked late into the night. A world expert on David, Professor Philippe Bordes, will be a speaker at the 2017 Boston symposium.

The series’ second article featured an American New England painting from nearly the same time. Executed in 1817 by Robert Peckham (Fig.8), it portrayed members of the artist’s family in their rural Massachusetts parlor. The occasion was sad; it memorialized the recent death of the young girl, Elizabeth, shown standing at the mother’s knee. In this case, the dial of the tall clock was signed, but a listed local clockmaker of that name would have been too young at the time of the painting, so the clock’s origins are unclear. Titled The Peckham-Sawyer Family, the painting hangs at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The third article’s subject (Fig.9) dates back to Italy in 1537. Painted by one of the most revered Italian Renaissance painters, Titian (or Tiziano Vecelli, 1488–1576), the portrait portrayed the Duchess of Urbino. Besides Eleonora Gonzaga of Mantua’s luxurious costume and her watchful dog, the gilt clock, probably from Augsburg, was the only other adornment. The costly little clock served to verify her wealth and her competence to rule the Duchy during her husband’s exile.

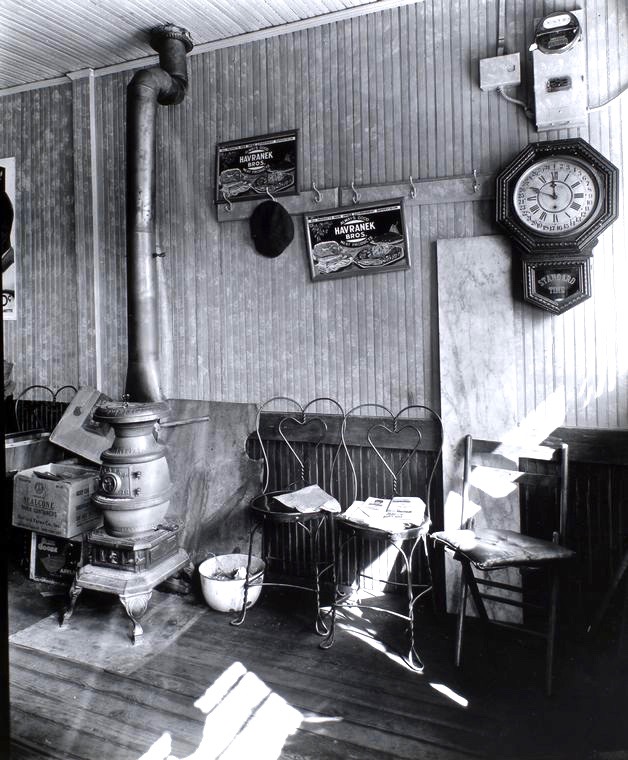

Photographs by some well-known photographers definitely qualify as fine art, and many of these are in my digital collection. My Part 6 focuses on a 1935 black-and-white image (Fig.12) by Berenice Abbott (1898-1991). She had a long and important career, and her photo of an old-fashioned New York country store revealed a Connecticut calendar school clock hanging on the wall.

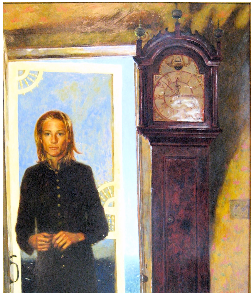

Part 26 features a painting (Fig.13) inspired by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s 1845 poem, The Old Clock on the Stairs. In 1868, Edward Lamson Henry painted this interior which Longfellow saw and confirmed to the artist that it truly captured the scene the poet was evoking. The painting was a popular attraction at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.

I will not continue here to summarize all of my articles, or list the hundreds of other horology artworks that await their turn for special attention. More than 100 images will be projected and discussed during my presentation at the Bamberg, Germany, meeting on October 7, 2017.

Of course, I cannot personally own these kinds of museum-quality paintings, but I have been able to acquire a few of modest value. My Part 23 article describes a watercolor by John Whorf (1903-1959), an admired Massachusetts artist whose “Abandoned Farm No.2” (Fig.10) I was able to purchase at a Boston auction. I also own the subject of Part 14, an 1860 Yokohama print (Fig.11), which allowed me to discuss other Japanese woodblock prints showing their distinctive style of clocks. In my colorful print, the artist attempted to portray a Western scene, along with a wall clock more European in appearance.

In a final look at my article series, I can mention Part 25, a c1881 watercolor by Winslow Homer (1836-1910). In 1992, I chose “Bell-Time Clocks” as the name of the antique clock repair and sales business I was opening. I had just bought a Homer engraved illustration titled “Bell-Time,” published in 1868 in Harper’s Weekly magazine, and the name sounded perfect for my enterprise. The print did not show a clock, but portrayed a mill bell tower and a crowd of textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, the city where I was living. After that, I searched long and hard for a Homer with a clock, and finally discovered a watercolor (Fig.14) at Texas A&M University’s Forsyth Gallery. Although the young woman’s identity is unknown, she is about to wind an 18th-century grandfather clock. The reason for the cello in the picture also is unknown.

Clock images also may be found in very early tapestries. In “Los Honores,” immense Flemish tapestries woven around 1523 for Emperor Charles V, I discerned at least three clocks, including the one shown in Fig.15.

There are not solely clocks in my image collection. Watches appear, too. They may be harder to see, but they usually are there to carry the same symbolic messages. Watches are particularly important objects in Dutch vanitas paintings by “Golden Age” still-life artists such as Pieter Claesz (1597-1660) and Willem Heda (c1593-c1680). The watches join the paintings’ other reminders of the quick passage of time and our need to make the most of it. For horology researchers, the finely drawn images allow us to see details such as fusees, hands, bells, pillars, pierced case covers and balance cocks, and more. Fig.16 shows such details in a 1663 Dutch painting by Willem van Aelst. Even marine chronometers have appeared, as in this detail (Fig.17) from Robert Davy’s c1783 portrait, John Arnold & Family.

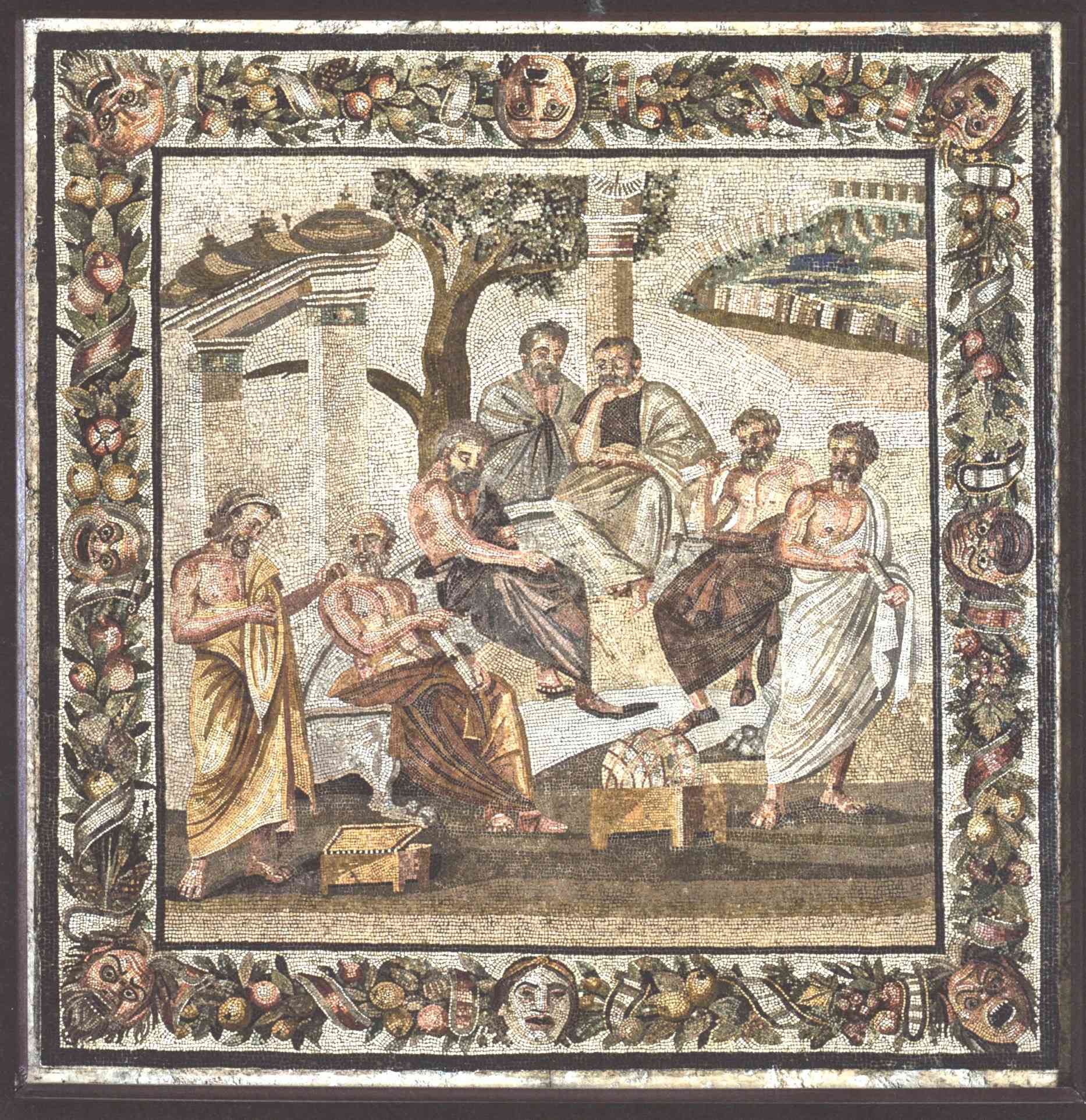

Until recently, I described my subject as 700 years of art with timepieces. However, an exhibit at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World carried me more than a thousand years further into the past. The exhibit, Time and Cosmos in Greco-Roman Antiquity, presented actual timekeeping, astrological and calendar artifacts from ancient Greece and Rome. Several of these objects were sundials, which are the most common instruments still extant from those eras. To my delight, there were not only large stone sundials, and small bronze portable ones, but mosaic depictions of sundials. One, from the 4th century, shows a man rushing to dinner past a pedestal-mounted sundial. Another (Fig.18), probably 400 years older, shows “Plato’s Academy,” with a sundial visible behind the Seven Sages.

Alfred Chapuis, I am sure, would have had much more to say on all this. In his spirit, I continue my discoveries, research, writing, lecturing and conference organizing on the theme of De Horologiis in Arte.

The following article by Bob Frishman was prepared for German translation and publication by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie in its 2017 Yearbook.

Click to view all of Bob Frishman's "Horology in Art" articles.

Fig.1

Fig.2

Fig. 3

Fig.4

Fig. 5

Fig.6

Fig.7

Fig.9

Fig.10

Fig.12

Fig.14

Fig.15

Fig.17

Fig.13

Fig.16

Fig.18

Fig.11

Fig.8